I grew up in Dayton, Ohio and entered the US Army in Richmond, Virginia. I spoke midwestern-American English. During my school years I learned a lot of Latin as an altar boy at church. In grade school they tried to introduce us to French. I got pretty good at reciting the Latin mass (Pre-Vatican II) but I don’t think I really ever learned what I was saying. It was rote.

In Catholic high school in the 1960’s I was required to take two languages. They wanted us to take at least two years of Latin and then two years of either French or Spanish. However, if you signed up for four years of Latin you only had to take one year of another foreign language, and one option was Greek. In those days I was really into Archaeology, I was in pre-Seminary, (one VERY, VERY, LONG SEMESTER!) and I thought studying Greek would be cool! So I opted for a year of Greek in my Junior year. In retrospect it’s still ‘all-Greek to me’ – but it does help with crossword puzzles.

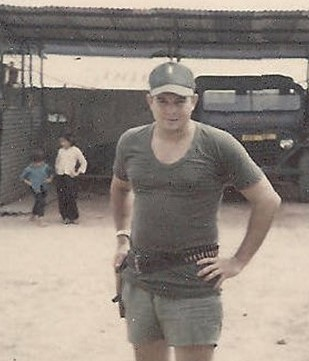

In 1969 I found myself as a 20 year-old Second Lieutenant and after commissioning and my Officer Basic Course at Fort Holabird, Maryland I was sent to Panama to attend the Jungle Warfare School prior to being sent to Vietnam. There we had a very brief course in the Vietnamese language. It was all military stuff:

“Where is your unit hiding? What kind of weapons are you using? What is your rank? Etc.”

Three weeks later I arrived in sunny Saigon as a replacement assigned to Military Assistance Command Advisory Team 85 in the Mekong Delta. I think that my non-military Vietnamese vocabulary at that time was limited to please and thank you and where is the bathroom! A couple of weeks later I was sent to Vũng Tàu to school for two weeks. Here we did get some rudimentary language training, but we were told that we would probably have to learn a lot more on our own. Most of what we learned was how to tell if our interpreters were honestly interpreting for us. We were warned that many of them were teenagers right out of high school who had taken English. However they were never really checked out for real ability before being assigned to us.

“Mr. Slim”, who I mention in my books, a young man who had been assigned to us, was a bit older and his English was pretty good. He worked with me to improve my language skills, and I assisted him with his American. We were a good team.

Now Vietnamese isn’t an easy language to learn for most Americans. It’s a ‘tonal’ language with actually a relatively small vocabulary. While there are about a total of 30,000 words most Vietnamese will only use about 5,000-8,000 in their daily life.

Compared to English that is a very small vocabulary. English has over 1,000,000 words and most of us use between 250,000 and 500,000 of them!

One of the biggest issues with Vietnamese is that while the ‘words’ are fairly standard there are a large number of local dialects, especially in the rural areas where I operated along the Cambodian border. When I operated in the northern part of Vietnam on my final tour the Vietnamese would laugh at some of my pronunciation. It was like a kid from the deep-South in the US going to Boston and trying to communicate; the words might be the same, but my pronunciation was laughable to them.

Because we operated along the Cambodian border I ended up learning a smattering of Cambodian along with Vietnamese.

My biggest advantage was that I had a great interpreter and my Sergeant and Captain both spoke Vietnamese learned during their previous tours there. We also lived in a Vietnamese home with our counterparts, and I learned what I called ‘survival’ Vietnamese at the dinner table. Total emersion was beneficial.

One had to be very careful when using some words because they had to be pronounced exactly or they could mean a number of things based on how you pronounced the word. It’s like; there, their, they’re in English. The word bà for example can mean a married woman, or anything female. It depended how you said the word. You definitely didn’t want to refer to the wife of your counterpart as a cow or even worse a prostitute! (Although the written words were different! Mis-pronunciations could be easily made!)

However, I found that the Vietnamese loved the fact I was trying to communicate with them on their level. They would often snicker at my attempts, and many would shake their head and happily help me find the correct word or words. The villagers and soldiers that I dealt with appreciated the fact that I was trying to learn how to deal with them as individuals rather than using Mr. Slim for my communications.

By the time I moved to Moc Hoa, the province capital as the Province Senior Intelligence Advisor my Vietnamese was pretty good. I could almost communicate on a middle-school level.

One afternoon I was interrogating a prisoner. My interpreter was sitting to my side, and I was facing the prisoner. I asked him a question in Vietnamese, my interpreter restated the question in Vietnamese, the prisoner answered me in Vietnamese and my interpreter relayed the prisoners answer back to me in Vietnamese. All three of us laughed. Afterwards my interpreter would only speak up if I didn’t understand the prisoners answer or if my question wasn’t phrased properly.

I would always face the person that I was interrogating, and my interpreter would always sit to my side. I was talking directly to the person and talking directly to him/her. I always made sure that when they answered they were looking directly at me and not at our interpreter. I was conducting the interrogation, and not my assistant! I think that eye-to-eye contact helped in gathering valid intelligence.

Today I’ve lost most of my Vietnamese language skills. I can still remember some of the important words and I can still count in Vietnamese. I’ve been told by some veteran friends who have gone back to Vietnam it came back to them quickly. But, I’ve never had a desire to go back to Vietnam it’s changed and I’ve changed. Vietnam is a memorable part of my life but not necessarily a memory that I need to relive.

I will always remember all of the little kids that surrounded us in our compound. They would all be in their late fifty’s or mid-sixties by now. My counterparts are all gone. But I often wonder how those kids did as they aged. Did they look at us, the Advisors, as the evil people that I’m sure the government insisted that we were, or do they remember us as the kind and considerate men that we were? Do they remember sitting on our trailer watching ‘cao bồi’ (cowboy), or ‘cảnh sát’ (police) television shows on AFVNTV with us and sharing snacks with us through that window? Or did the communist government paint us to be evil villains to be hated?

I’ve noticed that a few of my blog posts have been viewed in Vietnam it would be interesting to hear what they have to say.

Regards, “Hardcharger”

If you’re enjoying these blogs please drop me a comment or if you have any questions that I might answer again submit a comment on the comment pages. I’m always glad to hear from you.

Again please take a look at all of my books that I have listed. They can be purchased from Amazon.com with the click of a button directly from the website. Until next week, Have a good one.

The Advisor Series:

- “The Advisor, Kien Bing, South Vietnam, 1969-1970. A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B09L4X5NQ3)

- “The Province Senior Intelligence Advisor, Kien Song Province 1970-1971; A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0BHL2XCX5)

- “The Hardchargers,” Vietnam 1972-1973; A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0C7SPR1JY)

- “The Tuscarora Trail” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0D3QY2GM6)

Check out my website for other books that I’ve written or edited.

Website: ptaylorvietnamadvisor.com

Leave a reply to Peter A. Taylor's Home Page Cancel reply