A number of times I’ve talked about operating in the Plain of Reeds (Đồng Tháp Mười in Vietnamese). Our entire provincial area bordered with Cambodia on the north and the Vam Cô Tây River on the east. The entirety of Kien Binh district was considered to be a part of the Plain of Reeds.

The entire area was as ‘flat as a pancake’ and an enormous swampy area. It was crisscrossed with small streams and a number of large and small canals.

The Plain of Reeds is a vast inland wetland. Most of the area we are discussing is now a part of Long An Province and Đồng Tháp Province in the country of Vietnam. When I was stationed there our province was called Kien Tuong with the Provincial Capital at the town of Moc Hoa (Moc Loi in my books).

At one time (pre-Angor Wat) the entire area was a part of a river system that was actually the main water route from Cambodia to the South China Sea. But over time the entire area silted in, and the early Khmer settlers abandoned the area. At one time it covered over 2.2 million acres. The French colonizers drained large parts of the Plain of Reeds and created a massive canal system in the area. The current government of Vietnam has created a large National Park to try and protect and conserve this interesting wetland.

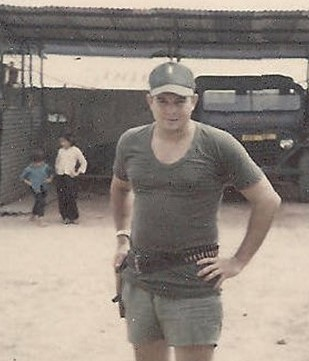

The Vietnamese name is Đồng Tháp Mười which means “The Black Swamp”. The soil is highly acidic as a result of centuries of rotting debris. During my assignments there my boots went from black to a grey patina. The acid in the water changed the color. While we could shine our boots if needed, we could never return them to their original color. But those boots became a mark of ‘experience’ especially when I wore them in Saigon.

One afternoon I was in Saigon and a very boisterous captain was bragging about his exploits. He was wearing a clean uniform with polished boots. When he saw me in my mud-stained uniform, the cleanest that I had, he started criticizing my appearance. The guy next to him took one look at my boots and told the captain he’d better lay off I was a “Delta Rat” from a place called “Rocket City”, That ended the criticism immediately. Those boots labeled me as a ‘warrior’ and not a Saigon staff puke!

In most areas that I worked the reeds were at least chest high or taller. We called it Elephant Grass. The blades had sharp sides and prolonged tromping through the reeds would tear your uniform to bits as well as cause minor cuts to exposed flesh.

Along the waterways Tràm trees, grew. “The Vietnamese used the wood from these trees: Commonly found in the wetlands of Vietnam, particularly in the Mekong Delta, this tree plays a crucial role in improving soil quality and providing habitat for wildlife. Its ability to thrive in waterlogged conditions makes it an essential component of Vietnam’s diverse ecosystem.” The natives harvested the wood for charcoal and collected the sap for its essence of oils. These essences were sold to perfumeries in Sagon or for export.

The area teemed with a wide variety of snakes, some of which were venomous. Other pesky critters were the leaches and a small white moth that would lay it’s eggs in the water. If you came in contact with the egg masses, you would develop a skin rash with small white pimple-like pustules that would itch and break open.

We had a number of waterfowl species that inhabited the swamps. These included ducks and ling necked cranes as well as hawks and vultures. Local hunters would bring fresh ducks to the village for sale. The further inland from the canals you would get the streams were clear and filled with colorful fish. If it hadn’t been for the constant threat of ambush, it would have been a beautiful area to enjoy.

There was one major road that followed the canal and the Vàm Cơ Tây river through our Province. The road (now National Route 62) was a gravel/dirt road that was impassable during the monsoon season. There were some small roads that were navigable in a Jeep during the dry season. One ran from Ap Bac to Tuyen Nhon. There was a US Navy Base in Tuyen Nhon. The other ran from Ap Bac west along the Grand Canal towards the village of Nhon Nhin One, the first of the three Nhon Nhin villages in the district. The other two villages were only accessible via boat even during the dry season.

A large single span bridge crossed the Grand Canal near our compound. It was a rickety old structure and during the buildup for the Cambodian Offensive a truck carrying soldiers and ammunition tried to avoid a broken stringer and got too close to the edge of the bridge. The bridge collapsed and all of the soldiers who were in the vehicle perished in the water.

Photo of Christmas 1969 celebration Bridge is in the background

The accident also destroyed the center span of the bridge. Initially the Engineers built a pontoon bridge across the canal. It was a real nuisance to the locals because the bridge was located at the junction of two major canals. The pontoon bridge made it impossible for boats to travel past Ap Bac heading ‘east’ towards the Vam Cô Tây River or west along the Grand Canal towards the Bassac River. For a short while the US Navy brought in a Mike/Tango (Can’t remember which) boat to serve as a temporary support base for the PBRs that were operating on the Grand Canal to our west.

The engineers were able to rebuild the center span quickly. They actually built the bridge frame east of town in a vacant area. When they had the span’s frame completed, they used a heavy lift “Skycrane” to lift the frame and place it on the undamaged piers. Once that was completed, they placed new decking on the bridge and by the end of the week traffic could once again cross the canal. They quickly removed the pontoon bridge and boat traffic could once again travel unfettered down the Grand Canal.

The only difficulty that we encountered was a near disaster for a portion of the town of Ap Bac on the north side of the canal. When the Skycrane came overhead the turbulence that it generated tore the roofs off of 40% of the village. As the advisor I had to take damage statements and reimburse the villagers for replacing their roofs. The next week many of the previously ‘thatched’ roofs were now covered with brand new corrugated metal, compliments of the US Government.

An old woman saw how much we reimbursed the villagers for repairing their roof. She claimed that as a result of the rotor-wash that she had lost a chicken, and she wanted me to pay her $20,000 US to compensate her for her loss. She figured that the wealthy Americans would pay her a lot of money for losing her chicken. We settled on three new chickens; she was disgruntled but satisfied. I threw in a carton of cigarettes, and she was happy!

There were two distinct seasons in Vietnam: Dry and Wet!

The Dry season began in November and ran through April. The period of October through November was transitional. The days were hot and sunny but occasionally we would still see some small amounts of rainfall. By November the dry season would hit us with its full fury. We went without measurable rain for five months straight. In April we would begin getting occasional showers.

It was during the Dry season that we saw the largest amount of combat operations. By November the swamps were drying out and the terrain was somewhat passible. Our largest influx of infiltration occurred during the Dry Season.

By May the Monsoonal season was upon us. It would rain heavily for the next five months. The canals would flood and much of the land was underwater. Movements were difficult except over the water in boats and sampans. In the built up areas the city streets would flood and were often impassable. Where the Dry season was hot and dry the Monsoon season was hot, humid and wet.

Road to the Airfield at Moc Hoa during the monsoons

We normally saw heavy rain three times a day. We would wake up to rain on the roof in the early morning, but it would generally clear up after sunrise. About two in the afternoon the rains would begin again and last until about four pm. It would then stop, clear up and be horribly hot and humid until about ten pm when it would rain heavily again. This went on for five months and then April would begin a transitional month with occasional showers until the season changed.

Life in the Delta for most of our Vietnamese villagers was fairly easy. The land that was farmed was extremely productive. A rice farmer could get between three and seven crops of rice out of a paddy each year. The entire area was loaded with fishponds where the locals cultivated fish for the market.

There were a number of unique ‘foods’ that we ate at Ap Bac. We ate most of our meals at our counterpart’s table.

The fish boat would come up the river from Mỹ Tho and bring us fresh fish in the live well. Our maid would go down to the dock and select fish from the live-well in the bottom of the boat. During the season we could get prawns, and a variety of fish. The other fish that they ate was called a ‘shit fish’. It was a variety of carp that was a bottom feeder. It was traditionally bake and served with the attached head and entrails served on beds of rice and seasoned with a spicy sauce called nước mắm (nook mom).

Another ‘exotic’ meat was Rat. Eating rats sounds gross to most of us and I was a bit ‘concerned’ the first time that I ate rat at our table. These weren’t ‘sewer rats’ like we think of in the states. Actually, they were more like eating a muskrat. They were caught in traps in the rice fields and their meat was somewhat gamy but actually pretty good. Usually, it was served in a stew or a thick rice soup.

We also ate snake, especially in the rainy season when it was difficult to get around and little could be bought in the local market. They would catch a large snake, remove the skin and cut two large pieces of muscle/meat from along the spine. The meat would be pulverized with a wooden mallet and then boiled for hours. It would then be combined with rice and vegetables for a stew of sorts. It was actually very tasty as long as you didn’t get a piece of snake that hadn’t been thoroughly pulverized. Eating that was like chewing on an old rubber band.

On festive occasions dog and cat were considered delicacies. Neither seemed to be kept as pets. Feral cats were kept around the houses to take care of rodents and snakes. Dogs were allowed to roam and were used as sentinels. Only Americans seemed to keep animals as pets.

We also ate a lot of chicken and pork.

What I learned about eating in Vietnam was that as long as the meal that was served was steaming hot, we had no issues with stomach problems. But there were times when eating at a small restaurant that I would send the food back to the kitchen if it wasn’t steaming. The other thing that I learned was to not ask what we were eating until after I had had some. It was an important lesson, you never wanted to offend your host!

f you’re enjoying these blogs please drop me a comment or if you have any questions that I might answer, again submit a comment on the comment pages. I’m always glad to hear from you.

Again, please take a look at all of my books that I have listed. They can be purchased from Amazon.com with the click of a button directly from my website, www.ptaylorvietnamadvisor.com. Until next Friday, Have a good week.

The Advisor Series:

- “The Advisor, Kien Bing, South Vietnam, 1969-1970. A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B09L4X5NQ3)

- “The Province Senior Intelligence Advisor, Kien Song Province 1970-1971; A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0BHL2XCX5)

- “The Hardchargers,” Vietnam 1972-1973; A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0C7SPR1JY)

- “The Tuscarora Trail” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0D3QY2GM6)

Check out my website for other books that I’ve written or edited.

Website: ptaylorvietnamadvisor.com

Leave a comment