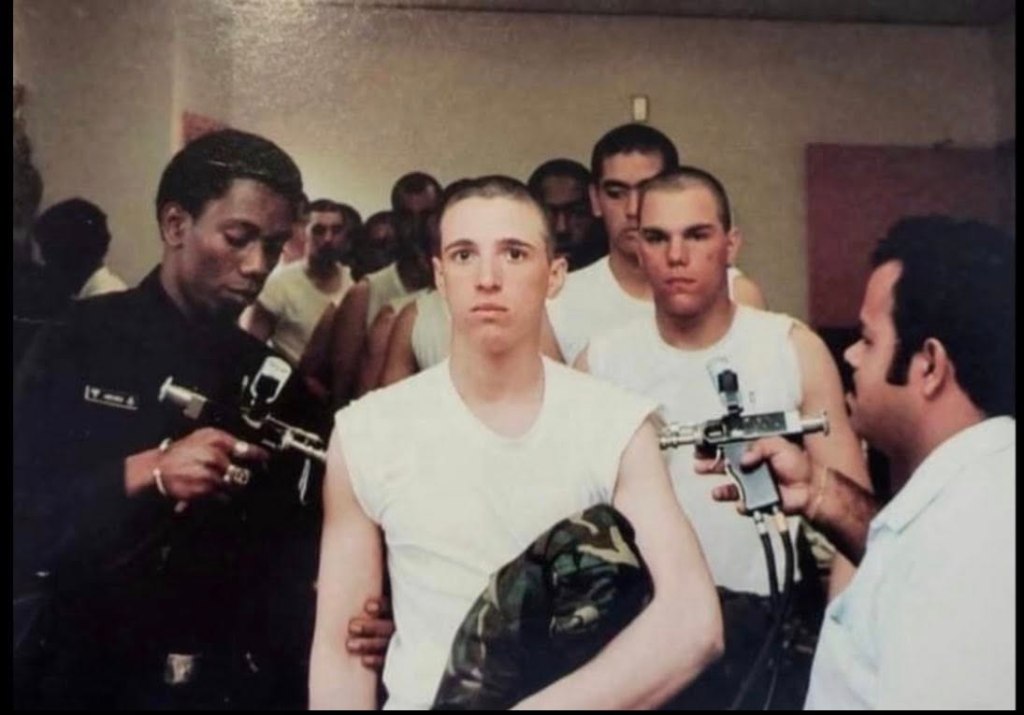

Most of us who were in the army in the 1960s can tell some interesting stories about medicine. I think one of the most ‘endearing’ stories deals with the infamous vaccination gun.

I can remember as a buck private standing in a long line of other soldiers and as you looked up the line you could see two medics one on each side with an unusual looking device in their hands. You would walk down the line until it was your turn. At that time, they would take this unusual looking device that resembled a gun in some ways put it up against your arm and fire. It usually happened simultaneously, with two guns blazing. Welcome to the wonderful world of getting your initial inoculations. To this day I have no idea how many inoculations we actually got at that first time through the line, but I do know that a lot of us didn’t feel very well for a couple of days. In one instance one of our soldiers actually fainted or passed out when he got the shots.

As I understand it the Medical Corps finally decided that too many soldiers were getting infections from these devices and ultimately, they stopped using them. I was told by a medic one time that you could get up to seven inoculations in each arm at the same time. It was definitely a weapon of mass biological destruction.

Note: Not my photo, but this gives you an idea of ‘the gun’

When I was preparing as a young Lieutenant to go to Vietnam, I had to go in see the medics and get up to date on my shots. We all had this little yellow shot record that we carried with us so that they could record the vaccines that we had been given. Somewhere in my files I still have mine, and its amazing how many pages are filled out. We would receive shots for all different types of tropical diseases, plague, yellow fever, and who knows what else.

When I got hurt in Vietnam, they gave me a tetanus shot. I’m certain that that was absolutely necessary at that point. Not only did I mess my back up I also had some deep cuts from the barbed wire that surrounded our compound. A lot of that barbed wire was resting in the water of the canal. That was probably the dirtiest, most bacterially infected water that I think God ever created. The Vietnamese had their outhouses, or privies, right out on the edge of the canal. They would dump their human waste right into the water where I was injured.

But there were a lot of things that we dealt with that there weren’t any vaccines for. In the Delta we had a small white moth that hung around the water containers. They laid their eggs in the water and if you got the water on your skin, it would break out into little boils. These were very tiny bumps full of a white puss, and if you broke one of them it would infect your skin. It would turn into a rash in the area where the water had touched the skin. It itched terribly, and the medics would give us an ointment that was supposed to clean up the mess. I don’t really recall it working very well.

When we went to Saigon or to one of the major cities, we were always required to get a Gamma globulin shot and given a handful of tetracycline pills. These prophylactics were supposed to take care of any potential venereal diseases that a soldier could get while visiting the big city. We hated the G-G shots, you got them in the rear end, and they burned like hell going in. They burned for an hour or so afterwards. I guess it reminded you that you really were supposed to be good boys and avoid the bad girls while you were in Saigon.

As an officer on patrol, I was required to carry the morphine bag. It was a small box of morphine syrettes, and I had to be accountable for every one of the syrettes that we had with us in the field. I suppose it was an accountability issue, assuming that the officers were less susceptible to misuse of this medicine. The two times that I actually had to issue it to our medic I had to make sure that the vial was broken and that I could account for how many had been used and at what time. Our medic would either use a magic marker or in some cases the blood from the injured soldier and mark a large M on their forehead to indicate that they have been given morphine. The concern was that too much would kill the person who was injured. If I recall correctly our medics only give two morphine injections in the field, the concern was that the third would kill the soldier. As I understand it an overdose of morphine stopped the breathing and heart rate.

My only real experiences with morphine were in the hospital during surgery. One time I was given morphine for pain. I just received a single dose; I can remember that it really brought on a state of euphoria that could become addictive.

Every week we had to take two malaria pills. One pill was a large salmon colored pill; we called it a ‘horse pill’ and we also used to refer to it as ‘Ho Chi Minh’s’ revenge. It was an antimalarial and it would give us a case of the trots, or diarrhea, for the day when you took it. We also had to take a little white pill once a day for malaria. Evidently, they didn’t all work the same way. On a trip up to the northern part of Vietnam I got bit by a mosquito and even though I was taking the pills that I was supposed to take in the Mekong delta they didn’t work up there and I came down with malaria. Fortunately, it was a very mild case but since it is a bloodborne disease I have not been allowed to give blood since then. I’ve had two or three recurrences of malaria over the years; they have been mild, but I can understand how bad the men who came down with malaria have it. It is something you never lose. You always have it in your system.

Even in Vietnam on occasion we would have to get new shots from our medic. We would get called up to the provincial headquarters and we would have to carry our yellow card with us. He would give us a shot and write down the type of medication, when it was given, and then hand us our shot card back. I have no idea what was in those vaccines, but evidently, they kept me fairly healthy.

As an advisor, I felt a real compassion for the infantry and field soldiers out there in Vietnam. We lived in a small village, in our counterpart’s house, and as a result we were able to maintain some degree of field sanitation. Our combat operations were generally very short, usually an ambush during the evening, or a sweep through a suspected infiltration route during the day. We could return to our village, have our uniforms cleaned and pressed and eat relatively hearty meals. Unlike the guys in the field, we didn’t live on C rations, but we did have to eat Vietnamese food. And as I’ve said in a number of my blogs, we insisted that whatever we ate was hot off the stove or out of the oven. The chances of it being infected went down significantly as long as it was hot off the stove or the oven.

One of the other advantages that we had was that we did build our own shower and bathroom facility. We had a 300-gallon plastic water tank on top of the tower that we were able to fill and add disinfectants to the water. The black tank would absorb the heat from the day, and we could actually take a relatively warm shower every day. Our house maid did our laundry daily and so our clothing was clean and somewhat sanitized. Compared to many of the combat soldiers in Vietnam we were living the life of luxury. Of course, we did not have the security that they had of being surrounded by large numbers of soldiers. There were three of us and we had to rely on our Vietnamese counterparts for our safety.

In the event of any really serious illnesses or injuries we could call upon the US Navy from their naval support base that was about 10 or 12 miles from our location to come and help out. When I got hurt in the barbed wire the Navy corpsman came down almost immediately and took care of my injuries and made the decision to send me to Saigon for treatment. Again, we were very fortunate with the medical support that we had available.

At the provincial level we actually had a hospital that was run by both the Vietnamese and the US government. These provincial hospitals had clinical capabilities. Each of them had a number of Vietnamese doctors and we would have an American Doctor and a medical team as their advisors. They could provide mid-range treatment and make the decision whether or not to evacuate the soldier to Saigon to the Third Field Hospital.

So while our medical care as advisors in Vietnam was rudimentary it did provide a higher level of care and treatment than what a lot of the guys in the divisional units found. My care in Saigon when I injured my back was excellent. I was at Third Field Hospital for roughly two weeks and then sent up to Long Bhin where I spent another two or three weeks in physical therapy. At the end of my physical therapy, I returned to my team and I was able to complete my tour of duty there as well as an extension of an additional six months.

I must say that my time in the hospital in Saigon was interesting and ‘enjoyable’ because of the outstanding nursing staff that we had to deal with. Those women were fantastic. I think that any soldier that dealt with army nurses felt the same way; they were angels in uniform. I’ve run into a couple of them over the years and I let them know how much we appreciated the loving care that they gave to us. They lived with the blood and the gore and the guts every day and how some of them survived the psychological stress I don’t know. I thank every one of them they are truly American heroes.

The same goes for every one of the combat medics, doctors, medical advisors and medical staff that we dealt with in Vietnam. True heroes one and all.

Regards, “Hardcharger”

If you’re enjoying these blogs please drop me a comment or if you have any questions that I might answer, again submit a comment on the comment pages. I’m always glad to hear from you.

Again please take a look at all of my books that I have listed. They can be purchased from Amazon.com with the click of a button directly from the website. Until next week, Have a good one.

The Advisor Series:

- “The Advisor, Kien Bing, South Vietnam, 1969-1970. A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B09L4X5NQ3)

- “The Province Senior Intelligence Advisor, Kien Song Province 1970-1971; A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0BHL2XCX5)

- “The Hardchargers,” Vietnam 1972-1973; A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0C7SPR1JY)

- “The Tuscarora Trail” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0D3QY2GM6)

Check out my website for other books that I’ve written or edited.

Website: ptaylorvietnamadvisor.com

Leave a comment