To My Readers: This is a conclusion of a short story taken from one of my unpublished works, “The Second Wisconsin Veteran Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, 1861-1865. I am going to serialize the story over a four day period. I hope that you’ll enjoy these posts in my blog.

Part Four

The Saga of Lieutenant Lancaster

In our previous post Lieutenant Leonard L. Lancaster had been convicted of mutiny by court martial. His men had done everything that they could to free him prior to his execution. His Chaplain had petitioned General Custer for leniency and had even gone so far as to ask Custer’s wife, Libby, to intervene on Lancaster’s behalf. In the final days of his confinement they had even organized a plot to free him from his jail cell and provided him with a horse, weapons and money to aid in his escape. He had refused, on his honor as a gentleman, to accept desertion as a means of saving his life, Our story continues:

About 5:00 p.m. the bugler sounded “boots and saddles” and all five regiments assigned to Custer’s Division mounted and marched fully armed and equipped on dress parade. They were formed in a hollow square about a mile from town where the executions were to take place.

An hour or so earlier Lieutenant Lancaster and Private Wilson were led from the jail by the Sergeant of the Guard. Their heads were hooded, and their hands were tied behind their backs. They were led to a waiting wagon drawn by a team of four gray horses. In the open bed of the wagon sat two coffins. Each man was seated on the end of their respective coffin. Major Lee, the provost marshal, was in charge of the arrangements for this execution; whether or not Major Lee was aware of the eventual outcome of this execution is not recorded, although Libby Custer indicates that he was in on Custer’s eventual plan.

The wagon with the condemned seated on their coffins was driven to the site of the execution. When they arrived there the wagon was driven around the entire command so that all might view those to be executed and learn a lesson; the fate of deserters and mutineers.

When the wagon stopped in front of the open graves, the men were ordered to stand while their coffins were off-loaded and placed next to the burial site. Once the coffins were situated, each man was ordered to kneel on it. Chaplain Brisbane came forward and prayed with them.

The firing squad was assembled. It consisted of twelve men and a reserve. As is the custom for men on a firing squad, their weapons were not carried but were handed to them once they were in formation by another soldier. Eleven of the weapons were loaded with full charges. However, one weapon only had a “blank” cartridge. None of the men on the firing squad knew for certain if they had a loaded weapon or the one with a blank charge. Each man could go to their grave with a belief that they had fired the blank round rather than one that had killed a fellow trooper.

Major Lee read the final warrant for the execution explaining the charges and the final sentence to each of them. Once the chaplain finished praying with the condemned men, he stepped back to the ranks. General Custer and his staff moved forward to a position immediately behind the firing squad.

Major Lee, the Provost Marshal, read the final warrant for the execution explaining the charges and the final sentence to each of them.

With a final nod of approval from General Custer, Major Lee gave the final orders to the firing squad;

“Attention”; “at the Ready”

At the command “at the Ready” the firing squad took aim at the prisoners and waited for the command “Fire” to be given.

Before giving the final command Major Lee stepped forward to the kneeling Lancaster and pushed him into his open grave and then commanded “fire”.

Private Wilson, of Illinois, a simple farm boy with no previous record of any violations of military law died instantly with seven gunshot wounds, but the dazed Lieutenant Lancaster was saved from his execution at virtually the last second.

A dazed Lancaster was ripped from his would be grave and fell at Major Lee’s feet. Was he dreaming in his instant of death, of salvation? But he realized that he was breathing and alive. Only General Custer and Major Lee knew of this last minute reprieve.

Lancaster’s redemption wasn’t due to any magnanimous gesture by General Custer. Custer would have executed the young officer had it not been for the undue pressure put upon him by a number of people. Major General Washburn’s intervention probably carried the most weight but Lieutenant Colonel Dale and even Mrs. Custer may have been the key players in saving his life.

When he was revived, Major Lee explained to Lancaster that the General believed that he had been the victim of undue influence and had long since determined upon the pardon; but some punishment he thought was necessary. Sparing the Lieutenant at the very last minute, the General felt, would demonstrate to his soldiers that he had not been intimidated from performing his duty because of the threats against his own life.

Another question that remained unanswered by the reprieve was if the men of the Second Wisconsin would have tolerated Lancaster’s execution; their carbines were loaded, and God only knows what the result would have been if Lancaster had been shot that day.

Lieutenant Lancaster’s sentence of execution was commuted. He was given a dishonorable discharge and sentenced to confinement in the Dry Tortugas for three years. However, the men of the various regiments saw this event as General Custer grandstanding with the life of one of their very own. Their hatred for their commanding general intensified. Rather than evoking fear in the hearts of the officers and men and impressing upon them his iron-willed form of discipline, General Custer only increased the discord and disharmony of the regiments under his command.

Lieutenant Lancaster’s ordeal did not end until the following March of 1866. After he was saved from the firing squad, he was sent to New Orleans where he was held in the old police jail for a time. From here he was transported on board a steamship to Pensacola, Florida, along with twenty-two other prisoners and two hundred cavalry. From there they went to St. Marks’. The prisoners were handcuffed together and placed forward on the open deck of the steamer during a terrible storm. The storm was so intense that if forced the steamer back to shore at Apalachicola for provisions and additional coal.

The next day they departed Apalachicola and finally arrived at the Dry Tortugas. This small island was located in the Gulf of Mexico about sixty miles from Havana, Cuba. The island itself covered thirteen square acres and was covered by the old fort and a small amount of vegetation. There were nine hundred prisoners on the island and three companies of regular army soldiers and their families.

Lancaster was assigned duties as a clerk in the adjutant’s office and then he worked for a time for the provost marshal.

After the mustering out of the Second Wisconsin Veteran Volunteer Cavalry, some of Lieutenant Lancaster’s old comrades petitioned General Sheridan to have the young man released. Others in the regiment had sought the assistance of General Washburn, who had recently been elected to Congress, and other elected officials. On December 1, 1865, General Sheridan authorized the publication of Special-Order No. 120 to release the young lieutenant.

SPECIAL ORDERS

No. 120

HEADQUARTERS

MILITARY DIVISION OF THE GULF,

New Orleans, La., Dec. 1, 1865

[Extract.]

- L L. Lancaster, Co. L, Second Wisconsin Cavalry, now at the Dry Tortugas undergoing a sentence of a general court-martial, commuted, is hereby relieved from his imprisonment, and will report to the Chief Mustering Officer for the State of Wisconsin, at Madison, for discharge, his regiment having been mustered out of service.

The Provost Marshal General of this Military Division is charged with the execution of so much of this order as refers to his Department.

The Quartermaster Department will furnish the necessary transportation.

* * *

By command of MAJOR GENERAL P.H. SHERIDAN

GEORGE LEE

Assistant Adjutant General.

Lancaster was finally released in February and returned to Eau Claire, Wisconsin, on March 3, 1866, four months after the mustering out of the regiment. He had received a dishonorable discharge from the service. However, twelve years later the condition of his discharge was changed to an honorable discharge through the intervention of Congressman Herman L. Humphrey. Congressman Humphrey succeeded in getting congress to pass a bill of relief, restoring his right to back pay, bounty, and privileges as a veteran.

Ten years after his release, in late July 1876, Leonard Lancaster was reading the newspaper and the terrible announcement regarding the massacre of the Seventh Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Big Horn by the combined Sioux and Cheyenne tribes.

Lenny leaned over and kissed Rebecca and smiled.

“You know darling that SOB tried to kill me in Louisiana and I lived to see his demise. God is truly good and just. I pray for the soldiers that were killed in the battle, but not for the man who tried to end my life.”

Leonard Lancaster of Eau Claire Wisconsin lived a long and prosperous life. He outlived his tormentors and attended all of the annual reunions of his former regiment. He was a staunch member of his church and often visited his old friend Chaplain Brisbane, the man who he was certain saved his life and strengthened his faith in God.

When Lieutenant Lancaster passed away in his sleep he was honored with a veterans funeral. Two of the men, his old ‘pards’, who carried his coffin had been men selected to form the firing squad that was supposed to plant him prematurely in a grave in Louisiana.

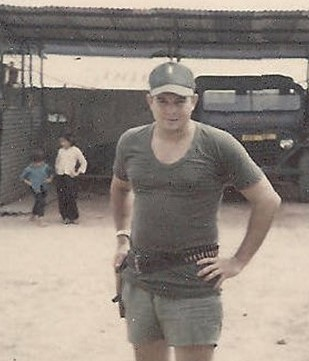

About the Author – Peter Taylor is a retired US Army Lieutenant Colonel. He served three combat tours in Vietnam between 1969 and 1973. He enlisted in 1968 and after Infantry Basic and Advanced Infantry Training he attended Engineer Officer Candidate School at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, where Taylor was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Military Intelligence Branch of the U.S. Army.

After his commissioning he attended the Military Intelligence Officer Basic Course at Fort Holabird, Maryland. Lieutenant Taylor was sent to the Jungle Warfare School in Panama prior to his initial assignment to Vietnam.

Taylor is a graduate of the University of Nebraska, Omaha. He earned a master’s degree in Management from the Florida Institute of Technology. Taylor attended numerous schools in the U.S. Army and graduated from the US Army Command and General Staff College, the National Defense University, and the U.S. Army War College.

Taylor retired from the U.S. Army as a Lieutenant Colonel in 1994. He is married to his wife of over 50 years and has three grown children and young grandchildren. After his retirement from the U.S. Army, he taught Junior ROTC at the high school level for seventeen years. Taylor and his wife currently reside in West Virginia.

Taylor is a military historian and has written a number of books on the Civil War. He was recently recognized by the State of West Virginia as a ‘History Hero’ for his work in recording the history of Harrison County and its importance during the US Civil War. He is the author of “The Most Hated Man in Clarksburg” a Civil War novel about Captain Charles Leib, his trials and tribulations in developing one of the largest Union Army’s logistical depot in Clarksburg, western Virginia in 1861-1862 at the very beginning of the US Civil War.

Website: ptaylorvietnamadvisor.com

Leave a comment