In my books dealing with my time as an Advisor in Vietnam I often talk about the CORDS Program. So, what was CORDS and where did I fit in as an Advisor and as a part of CORDS?

CORDS stood for – Civil Operations and Rural Development Support. It was a pacification program of the governments of South Vietnam and the United States during the Vietnam War. The program was created on 9 May 1967, and included military and civilian components of both governments. There were about 3,000 military advisors serving in the Mekong Delta when I was there. That averaged out to about 150 advisors per provincial team. As one of the smaller provinces we operated with fewer military personnel because we only had four districts (think counties in the US) to deal with and our team only consisted of three advisors.

This was just a fraction of the size of a standard 15,000-man Army Division. When I was stationed in IV Corps there weren’t any US Army main-line divisional units serving in the Delta.

The objective of CORDS was to gain support for the government of South Vietnam from its rural population which was largely under the influence or controlled by the insurgent communist forces of the Việt Cộng (VC) and the North Vietnamese People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN).

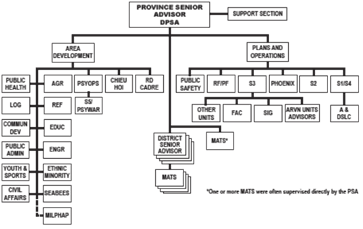

CORDS was placed under the control of the Military Assistance Command – Vietnam (MACV) and organized with the Province Senior Advisor in overall command. Provincial structures look like the organizational chart below.

By the time I arrived in the Fall of 1969 the Mobile Assistance Teams (MAT), shown at the bottom of the chart below, were being withdrawn. By January 1970 our four teams were gone and the only advisors serving in the four districts were assigned to the District or Province teams. Out three-man team was the smallest team in the province and an experimental team for IV Corps. Most teams had between 6-12 advisors. Most teams were comprised of a Captain as the District Senior Advisor, a Lieutenant as the Deputy and Senior NCO and specialists or sergeants serving as operations advisors or trainers. Most teams were housed in their own compound at the District Capitals. In our case at Ap Bac in Kien Binh District we were housed with our counterpart in the government headquarters building.

Standard Province Advisory Team

(Note: at District level we were at the bottom of the chart. When I moved to my position as the Province Senior Intelligence Advisor I was on the top line under the Military Plans and Operations as the S-2 Intelligence Officer. By the time I got there the MAT Teams were being phased out) .

A major priority of CORDS was to destroy the VC’s political and support infrastructure which extended into most villages of the country. The Phoenix Program was CORDS’ most controversial activity. Seven hundred American advisers assisted the South Vietnamese government in identifying, capturing, trying, imprisoning and often executing members of the VC infrastructure. Between 1968 and 1972, the Phoenix program, according to CORDS statistics, neutralized 81,740 VC of whom 26,369 were killed. 87 percent of those deaths were attributed to conventional military operations by South Vietnam and the U.S military.

As a Phoenix advisor I worked with both the military and the local police forces to identify and eradicate the Việt Cộng infrastructure. As I discuss in my first two books in the Advisor series this was a difficult process; getting the two agencies to work together. We were very successful in our operations and did significant damage to the infrastructure at the local and provincial level.

CORDS also did a lot of rural development. Some of them were very successful, some, not so much. In our Province one of the greatest assets that we had was the recuring visits by US Army Veterinarians. They would work with the local population to improve livestock through vaccinations and medical advice.

We also built schools and provided each hamlet with educational materials. Each month I would receive two large boxes that were designed to provide 100 soldiers in the field with three days of ‘sundry’ supplies.

“”SPs”, as they were known to those who served in the bush of Vietnam were treasured. The packs, which came out to us periodically, were rather large cardboard boxes that contained cartons of cigarettes, writing paper, envelopes, and ball point pens. I particularly liked the Chuckles candy, that I have not seen in years

There were other important items in these packs, …these items were soap, shaving cream, toothbrushes, toothpaste, razors and razor blades. This was before the throwaway razors.” Vietnam Veteran.

Since there were only three of us on our team we were swamped with all of this material and so we were able to donate most of it to our Vietnamese villagers. We would visit the villages almost daily and we would stop in and provide the schools with some of the writing paper, pens, pencils, envelopes and school type supplies. Each large box also contained cases of candy. When I went to the schools the teachers always made a big deal of my visits. They would have the children sing songs or read to me in English. (All of the schools in our district taught English beginning at about the fifth grade level). I would reward them with candy from the Sundry Packs. They loved the M&Ms as well as the Chuckles.

I haven’t seen Chuckles candy in years. I understand that there are still some stores that carry the brand, but; “Chuckles are jelly candies coated with a light layer of sugar. They come in five flavors: lime, orange, cherry, lemon, and licorice. Each package of Chuckles contains one piece of each flavor.”

During our visits we would usually stop at the local medical dispensary or Bác sĩ’s (Doctor) office and provide them with bottles of aspirin, anti-malarial medications like Mefloquine and Dapsone. We took the big orange pill once a week and the little white ones once a day. Dapsone is used in conjunction with other drugs for the treatment of leprosy. Apparently the US military was also concerned about troops, like us, near the Vietnam border with Cambodia contracting leprosy. So maybe they tried to accomplish two things with one pill. These pills may or may not have prevented malaria, but the Orange pill did give us a terrible case of diarrhea once a week. We referred to it as “Hồ Chí Minh’s Revenge”.

We gave the mid-wives shaving cream. They thought that this was a miraculous item. They used the foam to clean up after births as a disinfectant that could be applied directly.

We always carried candy from the Sundry Packs with us when we went up the canals to visit the villages. As soon as the kids saw us they would run to us asking for candy. This became a familiar sight as well as a distinct warning. If we entered a village and the kids didn’t come running out to see us we backed out quickly. It was a significant indication that there was some trouble in the village or hamlet, and we needed serious backup.

CORDS also provided us with medical assistance in the villages. They would send in teams of medical personnel to train midwives and work to improve sanitation in the villages. Our medical personnel would perform something called a MEDCAP visit to the villages. They would do rudimentary medical checkups, provide vaccinations, and treat minor injuries and wounds. CORDS also operated a hospital at the Provincial Capital called a MILPHAP (Military Provincial Health Assistance Program), created to improve the health of Vietnamese civilians.

A modern nationwide health care system did not exist in the 1960s in South Vietnam, so the U.S. government stepped in and funded a variety of health care programs during the war. MILPHAP was one of those programs. The others included the Medical Civic Action Program (MEDCAP), with doctors who visited villages; a Dental Civic Action Program (DENTCAP), providing dental treatment to the Vietnamese; the Veterinarian Civic Action Program (VETCAP), with U.S. Army veterinary personnel treating sick and wounded animals, vaccinating cattle and providing advice on feeding and caring for livestock; and the Civilian War Casualty Program (CWCP), which cared for Vietnamese with war-related injuries.

CORDS also came up with a number of programs to improve farming in our District. In two cases the experiments were a flop.

Raising pigs was a big source of income for many farmers. Most farmers would have a small pen and raise a couple of pigs for their own use. In some cases they would sell the meat to the local markets. It never amazed me how many local dishes were made with pork or pork products. Our morning bowl of pho (pronounced “fuh”) was made from pork broth containing small pieces of pork, and a variety of vegetables. Pork was used in a variety of dishes and served almost daily along side of chicken and fish.

So the CORDS directive required us to start an ‘industrial pig farm’ using US methods. I had to rent a parcel of land for the project near the town of Ap Bac. The ‘experts’ came in and built a large open shed with a concrete floor. Feeding trays were set up and a special diet of rice and another grain were fed to the growing animals. Watering troughs were constructed and finally weaned piglets were purchased, inoculated and placed in the ‘industrial pig farm’. I hired attendants (mostly young boys) to feed, water, clean the concrete floor, and care for the animals.

Within a matter of a couple of weeks the animals developed a serious problem with their hooves. Within a few days the first of the animals died and we called the Veterinarian and told him the problem. A few days later he made it to Ap Bac to investigate. Every animal eventually had to be put down. They developed an infection in the hooves that led to a type of septic poisoning.

Meanwhile the Vietnamese farmers were laughing behind our back at the American farmers. Later we found that local animals were usually covered in mud and the mud in the hooves prevented the infections that had killed our animals. The retained heat from the concrete floor was the culprit.

Another great plan was to mechanize rice production. The typical farmer plowed his rice paddies with a water buffalo and a plow. The paddy was extremely muddy, and the water buffalo was ideal for the plowing. Not only did they plow but the also fertilized with their dung as they plodded through the field.

To flood the field they would use their boat motor for a pump. Vietnamese boat motors consisted of a motor with a very long shaft that made it easy to navigate the small streams and canals in the Delta. These shafts were between six to eight feet in length with a prop at the end. To turn the motor into a pump they would simply remove and reverse the propeller, place the shaft in a long tube and reinstall the propeller so that it drew water from the canal through a long tube and flooded the rice paddy. Very simple but very effective.

So once again we were ordered to rent a one hectare (about 2.2 acres) of rice paddies so that the CORDS Agricultural team could demonstrate the American way of rice farming.

They brought in a special tractor that was used in the US to plow rice fields along the Mississippi River. I think it came from Arkansas IIRC. They organized the farmers to watch this machine quickly and efficiently plow the paddy. Within a matter of a few minutes the plow was mired in the deep mud. The Vietnamese organized a chain of water buffalos to help drag the machine out of the rice paddy. “Stupid Americans! And they didn’t even get any extra fertilizer!”

We then contracted with a farmer to use his water buffalo to plow the paddy in the traditional manner.

Next we brought in a special pump to quickly flood the field. Once again a group of local farmers were brought in to observe the miracle of modern technology. We started the pump and immediately began flooding the field, well for at least a few minutes. Within a few minutes the pump was clogged, and we had to remove the filters and unclog the unit. This happened every few minutes.

The Vietnamese pump was simple and had a significant advantage; the propeller would slice up the debris and shoot it out into the rice paddy. I hired the farmer to use his pump to flood my field.

Finally we planted the rice in the paddy. It was a new type of rice strain developed in the Philippines called IR-22 or miracle rice. It grew quickly and the Vietnamese were impressed. Within a matter of a few short weeks we were ready for our first harvest and the yield far surpassed what anyone had ever seen. We figured that we had finally succeeded in showing the Vietnamese how Americans could improve their production. The Civilian in charge of the Agricultural section at the Province headquarters was pleased after the first two failures.

There is a big difference between ‘paddy rice’ and ‘Miracle rice’. Paddy rice is glutenous and as a result when you cook it you can easily eat the rice with chop sticks. The IR-22 rice was a lot like ‘Uncle Ben’s Converted Rice’. Each rice piece was nice, white, and clean but very difficult to eat with chop sticks. So our Miracle rice ended up being sold at a very low price and used for animal feed – not the intended results!

“In February 1970, John Paul Vann, CORDS head in the IV Corps area (the Mekong River delta south of Saigon), gave an optimistic progress report about pacification to the United States Senate. According to Vann, in IV Corps a person could drive during daylight hours without armed escort to any of the 16 provincial capitals for the first time since 1961. Fewer than 800,000 people out of the six million people living in IV Corps were in contested or VC-controlled areas. 30,000 VC had defected under the Chieu Hoi program. In 1969, the number of refugees had declined from 220,000 to less than 35,000, and rice production had increased nearly 25 percent. Vann, a civilian after retiring from the army as a Lt. Colonel, had 234 American civilian and 2,138 military advisers under his command. More than 300,000 armed Vietnamese soldiers, militia and police in the Corps area were being advised and assisted by CORDS”

If you’re enjoying these blogs please drop me a comment or if you have any questions that I might answer again submit a comment on the comment pages. Glad to hear from you.

Again please take a look at all of my books that I have listed. They can be purchased from Amazon.com with the click of a button directly from the website. Until next week, Have a good one.

The Advisor Series:

- “The Advisor, Kien Bing, South Vietnam, 1969-1970. A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B09L4X5NQ3)

- “The Province Senior Intelligence Advisor, Kien Song Province 1970-1971; A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0BHL2XCX5)

- “The Hardchargers,” Vietnam 1972-1973; A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0C7SPR1JY)

- “The Tuscarora Trail” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0D3QY2GM6)

For more information visit Website: ptaylorvietnamadvisor.com

Leave a comment