The Chiêu Hồi (pronounced roughly as Chew Hoy) was an interesting program that I dealt with on a daily basis. In my book I talk about our “Man Friday”, Ông Hai, or Mr. Hai. He was our go-to guy as far as maintaining our Jeep, boats, trailer, generator, and almost anything else that we needed to have done. This gave us the freedom to serve as advisors rather than spending inordinate amounts of time taking care of day-to-day housekeeping tasks.

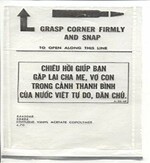

Chiêu Hồi Leaflett

Chiêu Hồi Instructions

On M16 Ammunition Bag

Mr. Hai was a former member of the North Vietnamese army who had defected in the northern part of Vietnam, subsequently surrendering and claiming “Hoi Chanh” status. He resided in the northern region of South Vietnam, specifically in Quảng Trị province, within an area along the Hồ Chí Minh trail under NVA control.

Drafted into the NVA against his will, Mr. Hai harbored no desire to participate in the conflict. He was a pacifist and adhered to a Buddhist sect that prohibited bearing arms. Consequently, due to his beliefs, he was assigned to labor-intensive duties, carrying heavy equipment, ammunition, and supplies along the Hồ Chí Minh trail.

One night, while they were resting, he heard a helicopter overhead. It was a South Vietnamese psychological operations unit broadcasting a terrifying story about a North Vietnamese soldier who had been killed in an artillery strike. His body had been torn to pieces in the attack. He was dead and his soul was wandering through the jungle looking for his head and other pieces of his body so that he could collect all of them and enter the afterlife. For Ông Hai it was a terrifying, ghostly story that haunted him.

As he looked up, he saw leaflets floating to the ground. His officers ordered them to collect all the leaflets and turned them over to them immediately. But Ông Hai hid one of them in his shirt.

The men in his unit were granted a three-day leave to celebrate Tet in their village, accompanied by their political officer to ensure their return after the celebrations.

During his visit, he went to see the monk and showed him the leaflet he had kept, asking for guidance. Mr. Hai couldn’t read; he wanted the monk to explain to him what the leaflet said. It explained how a soldier could escape from the fate of the ghostly tale that he had heard on that terrifying night.

The next night, when the Tet celebrations were at their peak, Ông Hai took his wife and children from the village. They walked over fifteen kilometers to the local South Vietnamese District military headquarters where he surrendered. After his interrogation by the local intelligence officer Ông Hai requested that the Resettlement Officer allow him to take his family to a place where he could work in peace without fear of being recaptured and punished for desertion or face reprisals against his family.

Ông Hai relocated to Ap Bac in Kien Tuong province, in the Mekong Delta where his wife had distant relatives. He first worked for the US Special Forces unit as their handyman and later joined our three-man team when we took over.

He was an excellent worker. He never learned much English and a lot of time we communicated through our interpreter, Mr. Slim.

Upon my arrival, he informed me that he would not clean any of my weapons. He stated, “A good soldier must care for their own weapon and no one else should touch it. That is a personal responsibility of a good soldier!” Additionally, he had vowed to the local monk that he would never take up arms again. He felt that even handling a weapon would be a violation of that vow.

Ông Hai kept our generators gassed up and running. He would help us with our boats keeping the gas cans full. When we needed to use the boat he would help carry the heavy motors and gas cans to the dock and install them. He kept our Jeep clean and did all of the preventative maintenance on the vehicle. When we were building our addition he laid all of the floor tile for us and assisted us in building the shower room/bathroom. He was a great worker, and we appreciated all of his effort.

In Chapter 27 of my book “The Accident” I describe how Ông Hai saved my life. When I was thrown out of the boat and into the canal, entangled in barbed wire, Ông Hai yelled for help and jumped into the canal to hold my head out of the water until Captain Wetherell and SFC Hartwick were able to free me from the barbed wire. Had it not been for Ông Hai’s quick action I might have drown.

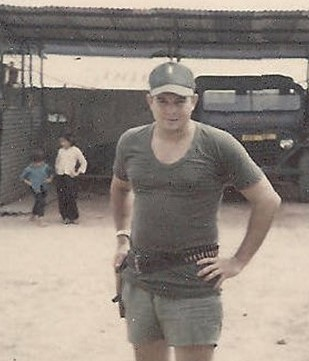

Ông Hai is leaning on the Jeep

While Ông Hai’s story was not unique it represented a large number of individuals who left the Việt Cộng or NVA and defected to the South Vietnamese government.

Many of these ‘deserters’ were interrogated and provided excellent intelligence about their units, equipment and intentions. We tried to debrief them as soon as possible to gather immediate and actionable combat intelligence on enemy strength, locations, intentions, armaments and leadership. In my case, as a Phoenix advisor, we were able to extract vital information from members of the local Việt Cộng regarding members of the resident Việt Cộng infrastructure.

Many “Hoi Chanh” continued military service. Some were assigned directly to US military units as “Kit Carson Scouts” or joined the Provincial Reconnaissance Units (PRU). The PRUs were often ruthless in their operations. They were often used to locate high level members of the Việt Cộng infrastructure or ranking enemy officers. Unfortunately, few survived these encounters with the PRU to interrogate.

The Chiêu Hồi program was successful. It was estimated that over 100,000 member of the Việt Cộng, VCI and North Vietnamese soldiers defected during the war years.

The South Vietnamese government offered a number of incentives to those who became “Hoi Chanh”. Like Ông Hai, many sought relocations to areas outside of where they were stationed in the military. They could have their families moved along with them and they could receive training and acquire job skills. In some cases they were also offered a cash ‘reward’ for actionable intelligence/information that they provided to the debriefers when they surrendered.

Overall, the Chieu Hoi program was considered successful. Many of those who surrendered made significant contributions to the effectiveness of U.S. units, and often distinguished themselves, earning decorations as high as the Silver Star. The Silver Star Medal is the third-highest US military decoration for valor in combat. The program was relatively inexpensive and removed over 100,000 enemy combatants from the field.

My son and a friend tried to locate my former team house in Ap Bac ten or twelve years ago. He was touring Cambodia and Vietnam. It was hard for him to find Ap Bac because the government had changed the name of so many places after the war. But they finally located the town and he and his ‘handler’ drove there. They tried to find someone that might be able to remember his father when he was assigned to Ap Bac.

They finally located an old man who was introduced as Ông Hai. He said that he had worked for the Americans during the war. He remembered a large man, he thought that he was an officer who was in charge of the American compound. He also remembered a young lieutenant who had an accident in the canal and that he had gone into the water to keep him from drowning. But that was all he could really remember.

He pointed out the location of the former District headquarters building. The old building was razed many years ago and is now the site of a high school. From the photos that I’ve seen of the place, all but one of the buildings I knew of are gone. One building that remained was probably our DIOCC site. Today the school uses it for storage.

From what I’ve been told life for Hoi Chanh’s after the war was difficult. Men like Ông Hai were sent to special reeducation camps. Some were placed into special units and given the dangerous task of removing minefield that had been set by the US, the ARVN and the communist forces during the war. Many fled to the United States with the ‘boat people’ or tried to get to Thailand or Cambodia.

It’s been reported that the men who served in the PRU or as Kit Carson Scouts received especially harsh treatment from the victorious communist forces. I have no idea of what treatment that my friend Ông Hai received but I can imagine that it was a very difficult transition for him and perhaps his entire family as well.

If you’ve enjoyed my Blog entry or have any comments of questions please leave a comment or please drop me a message or an email.

If you are a fellow Vietnam Veteran, “Welcome Home My Brother and Sister! We Made It!” Please pass this welcome on to any of our brothers or sisters that you meet. It’s the welcome that we didn’t get!

If you do purchase any of my books let me know how you liked them.

Thanks!

Pete “Hardcharger” Taylor.

MACV ‘69-‘71, 525 MI Group ‘72-‘73

If you’re enjoying these blogs please drop me a comment or if you have any questions that I might answer, again submit a comment on the comment pages. I’m always glad to hear from you.

Again, please take a look at all of my books that I have listed. They can be purchased from Amazon.com with the click of a button directly from the website. Until Friday, Have a good one.

The Advisor Series:

- “The Advisor, Kien Bing, South Vietnam, 1969-1970. A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B09L4X5NQ3)

- “The Province Senior Intelligence Advisor, Kien Song Province 1970-1971; A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0BHL2XCX5)

- “The Hardchargers,” Vietnam 1972-1973; A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0C7SPR1JY)

- “The Tuscarora Trail”(Available on Amazon ASIN: B0D3QY2GM6)

Check out my website for other books that I’ve written or edited.

For more information visit my website: ptaylorvietnamadvisor.com

Leave a comment