Another senior officer mentioned several times in my books is Colonel David Hackworth.

Colonel David ‘the Hack’ Hackworth, like John Paul Vann, was a controversial figure during the Vietnam War and had a military career spanning World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam Conflict.

David Hackworth joined the US Merchant Marine at the age of 14. He served onboard merchant ships in the Pacific theater towards the end of WWII.

At the end of WWII, Dave Hackworth enlisted in the US Army and served as an infantry rifleman in Italy on Occupation Duty. During the Korean War, Hackworth was recognized for his actions and received a battlefield commission as a second lieutenant. He was awarded three Silver Stars and three Purple Hearts for his service and injuries sustained in action.

In Korea, he was recognized for forming a counter-guerrilla unit composed of carefully selected ‘raiders’ to directly engage the guerrilla units they encountered. He became an expert in counterinsurgency operations.

When the Vietnam War began, Hackworth volunteered to serve as an advisor with the Vietnamese army, but his request was denied. It was determined that he had already accumulated more combat time than others, and his combat experience was needed elsewhere.

In 1965, he successfully secured an assignment in Vietnam with the 101st Airborne Division as an operations officer. During this assignment, he established a special operations unit known as “The Tiger Force.” Its mission was to function as a counter-guerrilla force aimed at surpassing the guerrilla tactics of their adversaries.

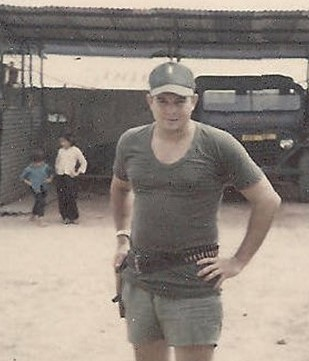

In 1970, I had the privilege of meeting Colonel Hackworth. He had recently been promoted and reassigned as the Commander of Special Tactical Zone 44, overseeing the provinces in the northern part of the Mekong Delta.

My initial meeting with Colonel Hackworth was quite significant. Our team had a newly assigned District Senior Advisor, a Captain. This Captain had been reassigned from II Corps after being relieved of command. An artillery officer, he had been involved in a ‘friendly fire’ incident where American advisors and their Vietnamese counterparts were killed. With the onset of the Vietnamization phase, there was a high demand for replacement officers. Consequently, he was reassigned to Military Assistance Command Team-85, replacing Captain Pete Wetherell (referred to as James West in the book), who had returned to the United States.

I had been in “temporary command’ for about a month when Pete’s replacement arrived. Captain S. wasn’t happy about the reassignment. As an artillery officer the ‘friendly fire’ incident ruined his career. He hated working with the Vietnamese and he definitely didn’t want to be there in the first place.

Shortly after Captain S. arrived, we got word that the new STZ-44 Commander was making the rounds of the various Districts, and he expected a briefing.

At approximately 1:00 pm, a helicopter arrived at Ap Bac. Captain S. picked up our guest and his Command Sergeant Major, bringing them to the team house. There, I was introduced to Colonel David Hackworth.

His Sergeant Major met with our Operations Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO), and they proceeded to address their responsibilities, which likely included gathering accurate information about the district. Meanwhile, Captain S. and I conducted the mandatory briefing. As the intelligence officer, I was the first to present after the introductions.

Our briefing room was a repurposed garage, furnished with a few chairs and a sofa. Colonel Hackworth chose the sofa, reclining comfortably with his feet propped on a small coffee table, as I commenced my briefing. Colonel Hackworth leaned back into the sofa, and I was concerned that my presentation might be causing him to fall asleep.

I made sure to keep him engaged during my presentation by pointing at the map and moving around. Despite these efforts, I suspected he might have been asleep. After finishing my briefing, I asked if he had any questions. He responded with three or four inquiries regarding operations in the base area, our interactions with the US Navy, and issues related to the Viet Cong Infrastructure (VCI) in the district. After addressing his questions, he commented ‘good briefing,’ and I handed over to Captain S. for his operations and political briefing. Captain S.’s presentation included a series of eight to ten graphic charts discussing the operational and political aspects of the district.

Captain S. began reading the charts to Colonel Hackworth. It appeared that Colonel Hackworth might be falling asleep.

After reviewing the third or fourth chart, Colonel Hackworth addressed Captain S. and remarked, “Captain, although I am wearing “crossed idiot sticks: (infantry insignia), I am capable of reading. Could you please explain the significance of these charts? I would like to understand your analysis of the situation rather than just hearing you read the charts.”

I intervened and clarified that the captain was recently appointed. Subsequently, I completed the briefing by addressing the Colonel’s questions.

I am not sure what happened during the ride back to the helicopter, but it seems Captain S. was given a specific directive. A few weeks later, Mr. Vann arrived, and after a contentious conversation between them, Captain S. was directed to depart with Mr. Vann and did not return.

There is an account I often recount regarding the maneuvering of a 105 mm artillery piece during an operation. We observed a Vietnamese driver and his assistant attempting to position the artillery tube between two banana trees to provide fire support to a unit engaged with the enemy.

The Vietnamese couldn’t get the truck to back the tube into position. The “Hack” yelled, “Somebody get that tube into position right now!” I took it as a direct order, got into the driver’s seat, gunned the engine and put the tube into place within a matter of a minute or two.

When I got out of the truck Colonel Hackworth made a comment; “that’s how you get it done!” I don’t think he had any idea that I had no idea what I was doing! I figured that the banana tree would snap like a twig if I hit it with that much weight, so I just gunned it and hoped for the best.

Sergeant First Class Hartwick, our NCOIC, advised, “Take action, Lieutenant, even if it’s wrong. We can fix mistakes, but not inaction!” He was a very wise Sergeant!

When I became the Province Senior Intelligence Advisor in Moc Hoa, I had frequent meetings with Colonel Hackworth. We always had to be prepared for his briefings during his visits.

On multiple occasions, I was sent to the airfield to collect him and transport him to the Province Senior Advisor’s quarters. Occasionally, he instructed me to send the jeep back and walk with him. During these walks, I provided him with a field briefing on the way to the compound. He expressed that he appreciated these informal briefings because they allowed him to ask questions that might not be raised or might seem inappropriate in general meetings. On one occasion, he humorously remarked that he wished to stop and stand next to a tree, mimicking a pose he had seen of General Grant receiving a briefing from his staff during the Civil War.

Colonel Dave Hackworth, a distinguished officer, retired after falling out with the Army. In Australia, he made a fortune in real estate and duck farming. Returning to the US in the mid-1980s, he worked as a military editor for Newsweek until his death from cancer in 2005.

Colonel Hackworth was an exemplary officer, and I gained considerable respect for him during my service in Vietnam.

Next week Vietnamese Counterparts!

If you’re enjoying these blogs please drop me a comment or if you have any questions that I might answer, again submit a comment on the comment pages. I’m always glad to hear from you.

Again, please take a look at all of my books that I have listed. They can be purchased from Amazon.com with the click of a button directly from the website. Until Friday, Have a good one.

The Advisor Series:

- “The Advisor, Kien Bing, South Vietnam, 1969-1970. A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B09L4X5NQ3)

- “The Province Senior Intelligence Advisor, Kien Song Province 1970-1971; A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0BHL2XCX5)

- “The Hardchargers,” Vietnam 1972-1973; A Novel” (Available on Amazon ASIN: B0C7SPR1JY)

- “The Tuscarora Trail”(Available on Amazon ASIN: B0D3QY2GM6)

Check out my website for other books that I’ve written or edited.

For more information visit my website: ptaylorvietnamadvisor.com

Leave a comment